Bartering in Balinese macaques

Springer link: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10329-017-0611-1

Sci-Hub: https://sci-hub.st/10.1007/s10329-017-0611-1

We've talked before about macaques before, in the context of Jessica Flack's work on complex organization and signaling:

And some macaques, like a pigtail macaque, which is one of the species that I’ve worked with, they have this history of fights with other individuals. And over that history, one individual will learn that it’s likely to lose to the other. And if the asymmetry between them is large, so that one individual knows with a high probability it’s going to lose, that individual emits what’s called a subordination signal. And it emits this signal outside of the agonistic or fight context, and it tells the receiver of the signal that the sender recognizes that it’s likely to lose, and has agreed to yield if a conflict in the future arises. The sender is agreeing to a subordinate state in the relationship. So this subordination signal summarizes, there’s a coarse-grained representation of that fight history, and then the two individuals use it.

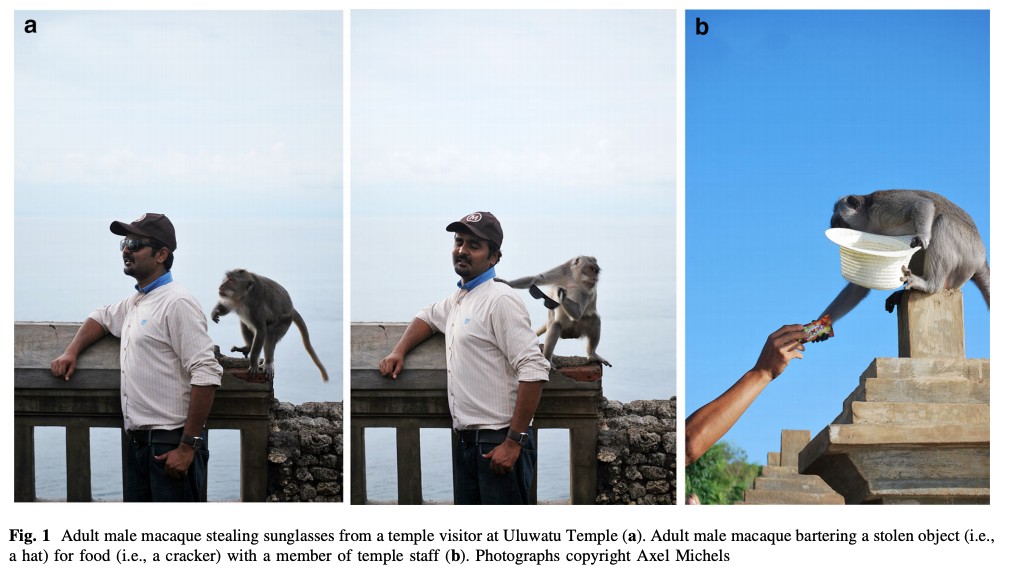

Now they've been caught exhibiting some pretty incredible behavior at the Uluwatu Temple, nabbing tourists' cellphones and valuables and then exchanging them for food. The paper's aims are pretty uninspiring, but the blow-by-blow description of macaques behavior is what's worth digging into:

our study is the first to focus on the spontaneous expression of RB events (i.e., the macaques initiate robbing events without any encouragement from humans), at least partially monkey-driven (i.e., even though bartering events depend on the willingness of humans to exchange, the macaques can choose to barter or not), and exhibited by a large number of free-ranging individuals

Anyway, if we're gonna refactor interpersonal interaction as bargaining—the idea tantalizingly raised by Schelling and then largely ignored by microsociology—animal analogues and capacities will be an important part of the picture.

suspendedreason

suspendedreasonHere's a link to Guardian coverage if you want the juicy bits without the dry rigor.

Shrewd macaques prefer to target items that humans are most likely to exchange for food, such as electronics, rather than objects that tourists care less about, such as hairpins or empty camera bags, said Dr Jean-Baptiste Leca, an associate professor in the psychology department at the University of Lethbridge in Canada and lead author of the study.

Looking at the data they pulled, it's hard to say how much this comes down to accessibility. Far and away the most common theft was sunglasses, which are easy to nab. Maybe there's some small effect, but it doesn't appear to be tested thoroughly.

In reply tosuspendedreason⬆:suspendedreason

In reply tosuspendedreason⬆:suspendedreasonOh and there's some amazing footage.

Of the bartering:

Of the robbing and bartering:

What's fascinating is that, despite being offered many sub-par goods, and being able to short-term defect by stealing off with many items (+the sunglasses or cell phone), they immediately return the items. They drive hard bargains, but are fair. This seems to imply they understand how to optimize over multiple, iterated encounters (vs just short-term exploiting).